Shape-Shifter

Mark’s migrations and self-recastings are as organic and unfettered as waves in the sea. From growing up in Yorkshire, to studying marine biology and oceanography in North Wales, to teaching secondary school and cofounding a production agency in Cornwall, his latest pursuit is turning the tide in UK’s surfboard industry.

Words by Beverly.

“It’s a slow build up,” Mark says on an early Tuesday morning in July, height of Cornish summertime. He is relaxed, seated on a picnic bench in the courtyard of Wheal Kitty Workshops, contemplating the ineffable allure of surfing. Behind him, his newest venture Open is quietly readying for the business day ahead. He continues, “You’re continually trying to master it. You find yourself in situations where you’re slightly out of your depth sometimes then, if you get through it, it gives you a raise of confidence to enjoy the easier stuff. You’ve got to put yourself right on the edge.”

Versed in the worthy thrills of methodical risk-taking, Mark’s entrepreneurial and surfing styles are well enmeshed: equally as tenacious as they are laissez-faire, single-minded as they are communal. Fortunately so. His latest endeavour is an elegant, human-centric business model that is transforming Cornwall’s surf retailscape, sustainably. “There’s a lot of talk about being environmentally friendly — which is good, it’s something we are definitely going to work towards,” he explains. “This isn’t an environmentally-friendly industry and we’ll do our best to work towards it — but I think people often miss the social aspects of it. The people behind it. It’s the whole picture, isn’t it?”

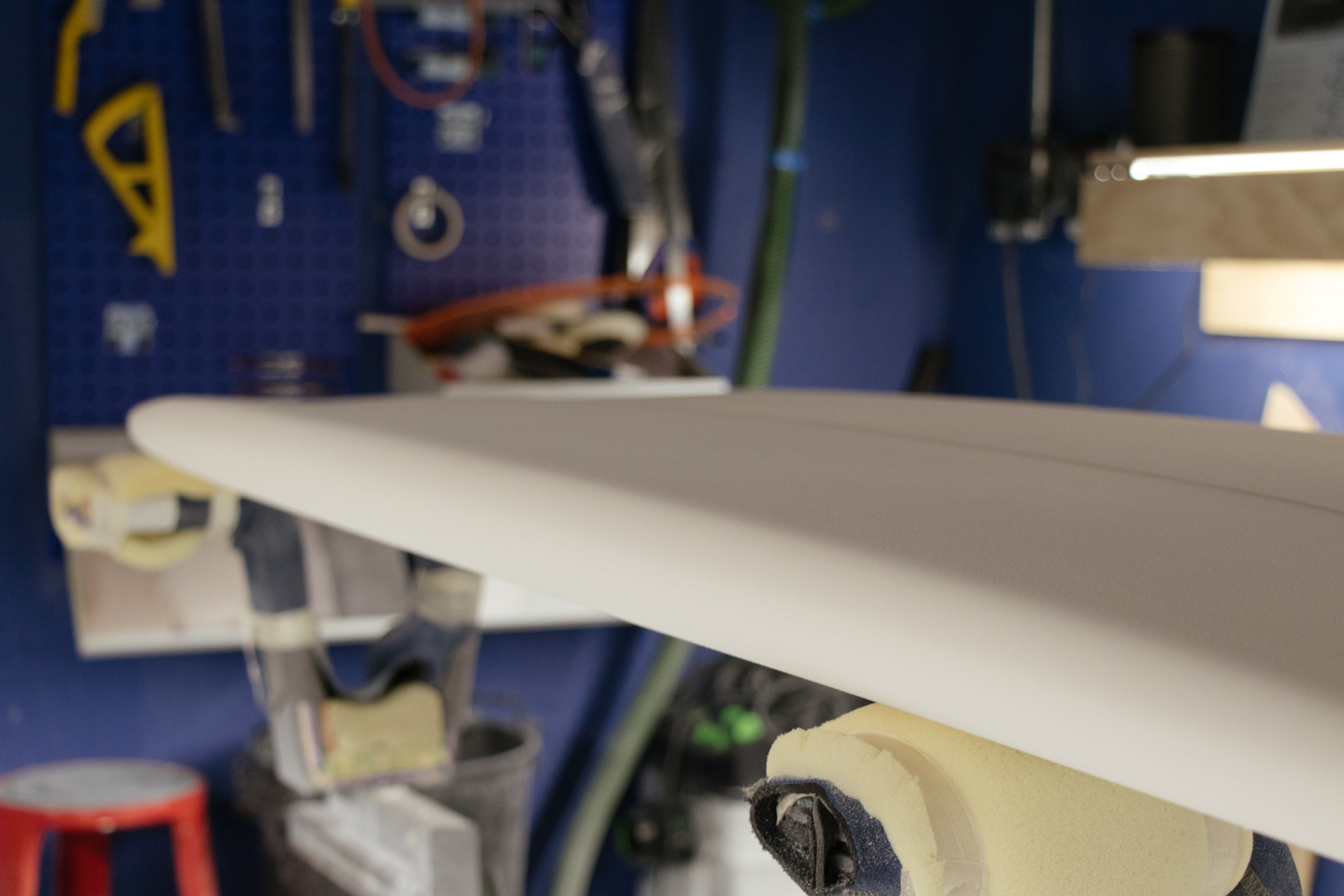

Above, Open at Wheal Kitty Workshops, St Agnes; a growing collection of demo boards, “We prefer to keep them grey so people look at the shape rather than the brands.” Below, Freddie unlatching the doors for the business day ahead.

Stepping inside, Open’s interiors are coolly unassuming. Muted colours and natural textiles backdrop monochrome surfboards and delicate greeneries. Scents of the ocean, fresh coffee, and sawdust breeze through. A large La Marzocco espresso machine sits comfortably at the bar next to a tray piled high with Mark’s own homemade flapjacks (aptly renamed “crackjacks” by the locals), while music drifts from discreet speakers and curated books are casually left open on side tables. The experience altogether would not be dissimilar to arriving at a friend’s stylish bungalow for breakfast if it wasn’t for a nondescript doorway in the centre of the room, luring the eye down a corridor towards the back where, within plywood-clad shaping bays, artistic chaos and unfamiliar machinery are deliberately displayed. Open is, after all, not merely a shop-cum-cafe but a functioning re-interpretation of a surfboard factory where made-to-order surfboards can be expertly crafted by international shapers, or handmade by the customers themselves. With neither an air of intimidation nor clique, seasoned and beginner surfers alike are welcomed by homely hospitality. “We wanted it to be: there are no silly questions. You can come in, chat boards with people, but you can also just hang out and read a book in the corner, you know?” Mark offers. “We want people to come in and feel like they can come in all the time without having to drop six hundred quid on a board.”

His community-minded approach is in good company here, where neighbours include the Finisterre headquarters, Canteen, Surfers Against Sewage, and Sideways (the media production agency Mark and his wife, Emily, founded ten years ago). As the day progresses, a steady stream of colleagues, friends, dogs, and surfers wander through, frequently exchanging cheerful “heys” and brief catch-ups. Around midday, lunch tables are assembled in the courtyard and ebullient groups gather under the heatwave sun. But it hasn’t always been this way. When Mark and Emily first considered the historical mining site in 2013 on their search to relocate Sideways, the buildings had been largely industrial and derelict. “It was a leap for us,” he recalls. “A drilling fluids company was in both units. Finisterre had one of them and the other had been empty for a year.” Today, tenancy at Wheal Kitty Workshops is waitlisted.

‘Surfers have to get better at understanding where their boards come from. Who has made it? Have they been paid fairly?’

It is no coincidence that a surfboard factory had once thrived, twenty-five years earlier, where Open now resides. With its front shutter often closed and its interior bays dark and poorly ventilated, by the time Mark and his spaniel discovered the factory in the mid-2010s while on a morning walk, the business had been collapsing under evolving retail expectations and rising popularity for mass-produced imports. The solitary shaper remaining at the site was preparing to fold up the business. Intrigued by the process, Mark began to return regularly, eventually befriending and confessing in the shaper how he had become so consumed with work that he no longer cared for surfing like he once did. The remedy, the shaper decisively proposed, was to make him a custom, handcrafted surfboard.

“I had always assumed that British-made boards would be a bit sh*tter,” Mark admits. “Like, why would a British guy know more than this [hi-tech surf] company that seems to invest loads in R&D?” He goes on, “But then I got to know him, and he was so good at what he did. All those years of experience that had gone into it. He made me this magic board that got me back onto a shorter board, and got me super amped on surfing again. That is what these guys have. The skill in knowing you. I just thought, f*ck, that is really good.”

In quick pursuit, hoping to keep the business afloat, instead Mark began to uncover the industry’s underbelly rife with greed, negligent working conditions, excessive waste – all at frustrating odds with mainstream surf culture. It furthered his sense of urgency. “I think everyone wants to know that people are being paid fairly. We have to realise that it isn’t happening at the moment,” he says. “As the people buying the boards, surfers have to get better at understanding where their boards come from. Who has made it? Have they been paid fairly?” Then in the same breath, agitation rising, “The polish is a great example.” He explains that when a customer requests a glass job (to polish a surfboard), his or her supplemental cost is typically around £30 in the UK. This fee is meant to cover a glasser’s six hours of required labour to achieve a glossy, perfectly shiny finish, before the factory takes half cut. The resultant wage for the glasser is £2.50 an hour. “It’s nuts!” he exclaims. “As long as we sell the board for the correct price, why do we need to take any more out of it if it’s someone else’s time? And why not just explain to people that it takes someone six hours?”

Neither purely rhetorical nor didactic, his questions seem to hold a deeper gentleness and timely faith in people. “It’s that thing, isn’t it,” he concludes. “If it hasn’t been done yet, if there is a problem, there has to be a solution.”

Above, Mark and Freddie behind the coffee bar while Ralph, Mark’s spaniel, lounges on the concrete floor; standing outside one of the bays; when the doors to the bays aren’t propped open, customers are welcome to peek in through looking windows. Of the interiors, Mark says, “When we thought about how to renovate this place, I thought Orbea-style: dark, motorbikey. And Em was like, ‘No. It’s gotta be white. Bright. As clean as possible.’ And I’m so glad we went down that route.”

Naturally, his solution is a refreshing response to business as usual. Devoid of a distinctive logo or tagline, focusing on low stock and mindful customer service, and removing the shop-as-middleman entirely, Open is tasking itself to become much less a brand than an exchange hub for local shapers to connect with a global audience. “There are loads of other shapers out there who can’t promote themselves,” he reasons. “We can promote the skills, promote them.”

Open’s impressive roster of guest shapers to date have included Simon Anderson, Neal Purchase Jnr, and Beau Young, each offering limited edition, hand-shaped surfboards available for order. “Everyone has a different style of surfing,” Mark explains. “We’re trying to keep a variety here” – and they have; in 2017, the venue hosted UK’s first Nixon’s ‘The Weird’ shaping challenge, where expert shapers (Hugh Brockman, Lee Bartlett, Luke Young, Chris Harris, Brad Rochfort, and Andy Gale) each crafted colourful, zany-yet-purposeful surfboards which were transported to the Cornish south coast and peer-judged in a friendly competition.

Mark has also recently launched Open Board Club, a flexible membership scheme which offers customers access to a growing library of handcrafted demo boards. Boards that are intended, unconventionally, to remain as rental boards until the end of their working lives – and which happen to be the only boards on display in the shop. “I’ve got this mental idea where those boards never get sold,” he says. “They just get rented and rented and rented, until they get to the point where they’re not surfable anymore, and at that point we recycle them. That surfboard is going to earn its value ten-times over, both environmentally and financially.” The merit of this system is two-fold. By carefully diversifying Open’s collection and allowing others to take them out on the water, Mark is also encouraging the public to make informed purchases, thereby reducing consumer waste and dissolving retailer pressure to carry and rid stock on customers. “People need to find a way to find that perfect board. We don’t want to flood the market with loads of second-hand boards. So we’re hands off. You can come in, try something, find out if it’s the right thing for you from the right shaper. Once you find something that’s right for you, it’s a whole different ballgame,” he promises. “It’s not a risk paying the money anymore because you know it’s right.”

Absent from their factory are “cookie-cutter, machine-made jobbies.” Opting for a labour intensive process, they are proudly crafting boards “like how people used to build boards in the 70s.” For their boards built to last, Mark hopes to soon launch Open’s online, collaborative platform via which customers can track their made-to-order boards from start to finish and onwards: shaping, laminating, filling, and finishing; all the materials invested; biographies of each shaper involved in crafting an individual board; then, customers, too, can personally upload pictures of their boards in-use. If a board is ever re-sold, the individual can still login to view updates from the next customer, to see how the next person is enjoying it. Such a platform would allow for personal ownership, value, spontaneity. “It’s about putting importance on the board,” he says simply, nudging product longevity one step further into a more sustainable future.

Then he quickly glances down at his eighties-style Casio watch strapped tightly to his left wrist, and suggests to take us on a tour of Sideways, across the courtyard.

Above, an organised chaos, everything has its place in the workshop office. Below, scenes from inside the various shaping and finishing bays, including Steve at work in the glassing bay; once dark and poorly-ventilated rooms, the new windows allow necessary air and daylight into the workspaces.

‘What’s hard here is, we are all making these businesses on a shoestring. We’ve done it with bits of savings, loans, and credit cards – and blood sweat and tears.’

‘It has been a lot of work getting the product right, and I feel like we’re just getting there now.’

Above, minimalism on the retail floor. Below, touring the offices at Sideways (Mark and Emily’s media production company) conveniently located across the courtyard from Open.

The story of Sideways begins with equal verve but, as Mark says with a laugh, more “arrogance.”

Mark and Emily had met in university; he had been completing his work-studies as a teacher and she her degree in graphic design. Together as fresh graduates, despite colleagues urging them to move to London, they knew they wanted to “start something up” themselves. Spotting a gap in the Cornish market for film-quality video production, he says, “We just bought a camera. I had some experience as an amateur videographer, she had an interest in it. That was it.”

With one camera and a strong vision, they set about doing things differently. In a pre-DSLR era, they began to construct makeshift solutions (“a news-style camera with a spinning disc contraption attached to it”) to create the shallow depth of field and grainy quality they had in their minds. Fortuitously, one of their first clients was design-forward Scarlet Hotel, then pre-opening. Mark tells the story:

We contacted a hotel up the road called The Scarlet that was just opening up. There had been a lot of investment in it, so there was a lot of interest in it already, but because Em went to uni with Ben Howard, the musician, we managed to get one of his tracks. We put that track on the film – and it just went mental. It was watched six hours a day for a year. So, that was the start of that. And it just built up through word of mouth.

Their winning ethos became about pushing boundaries and adding experiential value to brands through emotive storytelling. And after two years of juggling both careers concurrently, Mark was able to leave teaching behind to focus on the agency. “It sounds good,” he adds, “but it was f*cking hard because of our naivety.”

In those early years, their team of two quickly became a company of twelve, forcing Mark and Emily to learn how to run a business and to be video producers at the same time. “If I’d known what I know now about the industry, including what the rates are for proper work, it would’ve been such an easier journey. Not the same one, but easier.” He continues:

We made all the stereotypical business mistakes.

Down here, there’s a lot of EU funding that flows around and success of that is judged by how many people you employ. So, for years we thought success meant having more people on board because we got pots of funding — and to some extent, it’s satisfying employing more people, but it can also be a pain in the ass.

We got to the point where we were 12 people, but we weren’t doing the work we’d originally intended to do, because we were grabbing at stuff. We ended up saying yes to work because of the overheads, even though nobody wanted to do it. And the freelancers didn’t appreciate it because they weren’t doing good work. You spend your working career feeling undervalued a lot of the time. It’s not that clients don’t get you, it’s just that you’re constantly being pushed down on price and expectations. It was just not a positive thing. We lost our original reason for being.

It was only after making that mistake, I realised that that wasn’t success. It’s actually way better for us to have way less work and less people.

We’re much more of a pure production company now and we hire freelancers on a project basis, even though it costs us more at that point in time, but it takes the pressure off of having to say yes to projects just to cover overheads.

Ten years on, Sideways’ body of work has evolved along with technology, the team, and its leaders. Now ready to step back in order to focus on Open and their young family (three kids all under the ages of five), Mark and Emily have introduced an employee ownership scheme at their agency. The incentive plan beautifully mirrors the cycles and rhythms of life, encouraging younger employees to build their careers within the company: to experience the excitement of travelling, of working hard and building relationships with clients, of having a financial stake in its performance, then, when the time comes, of thoughtfully moving on as Mark and Emily are now, by passing knowledge and eventually their own shares – and the company entirely – on to others.

‘For years we thought success meant having more people on board and, it was only after making that mistake, I realised that wasn’t success.’

Standing amidst a row of surfboards, not far from the Sideways office, Mark faces a new hurdle at his second startup: “It’s been a lot of work getting the product right,” he says, “and I feel like we’re just getting there now. So the next question is, how do we engage with people?”

Cornwall’s outlying geographies and highly seasonal traffic demand a certain doggedness from retailer entrepreneurs. Thankfully, social media has shrunken our psychogeographical scale, placing distant or smaller locales like St Agnes, where footfall is comparatively low, within reach. “It’s funny how many people we’re getting here who’ve seen us online who are then like, ‘We had to come out and see it.’” Once here, off the beaten track, first impressions become vital as a surfboard’s buying cycle is four years. “We don’t need many people,” he says humbly, “we just need the right number of people. But if we’re not wowing everyone who comes through the door, we’re not going to build a business.”

Also hidden from view is the grit required to outfit and establish a new shop, particularly when opportunities for external funding are scarce. “What’s hard here is we’re all making these businesses on a shoestring,” he explains. “We’d done it bootstrapped, with bits of savings, loans, credit cards – and blood sweat and tears. We’ve put a lot of personal time and effort into ripping the place apart. So I’m 100% in it. And everyday I feel like there’s something I haven’t done yet.”

Above, Below, taking it easy in the main lounge, where an abundance of plants help to improve air quality and encourage a slower pace.

He remains undaunted. He is too busy wholeheartedly solving the next challenge, after all. Or, in some cases, cultivating unexpected opportunities. Freddie, for instance, is Open’s part-time barista, factory assistant, and plant specialist. Mark had met him briefly at a local event and had “really liked his personality, he’s got a welcoming thing.” As Freddie was also completing horticultural studies at the Eden Project, Mark had invited him to introduce plants in the workshops as air purifiers. “We loved the look of it,” he says, and happily placed Freddie in charge of ordering additional shipments to display throughout. The plants then took on a life of their own, changing the way customers engaged with the space, drawing them in and slowing their pace, encouraging them to browse. From fiddle-leaf figs to mini jade and zebra succulents, potted plants have since been added to Open’s selective retail collection and, these days, have become a staple. “They’re helping us to sustain the business,” Mark says proudly.

In one of the bays, Mark admires a surfboard blank, a work-in-progress by one of the shapers. “Cabinetmakers are always surprised by how little measuring we do, to get the curved form, the symmetry,” he says. “There’s an element of feel to it.” His hand skims across the smooth, dusty surface as he studies the form over. A faint, diminutive signature etched into the foam briefly appears under the fluorescent light. “I’ve always found it fascinating, watching the shapers work. And when you do it yourself, there’s this lovely moment where it all comes together and you look at it and go, I’ve actually made this thing. And they are things of beauty.” ▫

Photographs by Fields in Fields. Edited 1 June 2019; originally titled ‘Turning the Tide,’ published on: 1 April 2019. ▪ Visit Open, Unit 3, Wheal Kitty Workshops, St. Agnes, Cornwall TR5 0RD. For more info and prices, ring +44 1872 553918. www.open.surf