Outpost

Quick to highlight the absurdities that travelling can throw at you (how freeing and terrifying these can be!), Dan’s newest publication on remote settlements — both primitive and futuristic — reads like a delightful, provoking, probing stream of consciousness. Outpost: A Journey to the Wild Ends of the Earth’s spirited, disparate ensemble includes a caretaker at Ferðafélag Íslands, a researcher at the Mars Desert Research Station, employees at the Mountain Bothies Association in Scotland, a mountain guide in Tottori Prefecture, and more. Below, Dan chats about his writing process, humanity’s “questing nature,” and the delicate paradox of seeking transformative experiences in wild places.

Interview with Dan Richards, writer.

Hvítárnes, Iceland. Photographs: Dan Richards

Fields in Fields: To start I want to touch upon the immensity of this project: there was the necessary research before, during, and after each trip; your undertaking of the far-flung adventures; then having to organise and write about them. On pp.126-127, you write:

I chose to go to Utah in the next couple of years and do the other things (involved with writing this book), not because they were easy, but because they were hard; because that goal would serve to organise and measure the best of my energies and skills, because that challenge was one that I was willing to accept, one I (and my publishers) were unwilling to postpone, and one I intended to win...

Can you briefly take me through your process and how long it took you to write this book?

Dan Richards: First, I should say that the particular extract you cite is a reworking of J.F.K.’s Apollo speech, played for laughs; the word moon subbed out for Utah. Hopefully I made that clear in the text. I think there was a footnote to flag this but, either way, the immensity that you speak about exists at several levels in the book, stratum formed of the thinking, the research, the planning, the journeys, the text; the main text, the pictures, the subtext, the footnotes, the addenda, the bibliography… but above all, it starts with immediate lived experience set down by hand with pen and pencil in a notebook. My notebooks act as scrapbooks and places to refine my thoughts, the connective tissue of the book; the dodgem-logic of collisions which drive my books along. Later I write them up and then rework them again on my Mac, but a lot of the heavy lifting, sifting, and collage happens in my journals.

Outpost took two years to physically travel and write, I think, but I was thinking about it for a good year before that. The seeds were sown and germinating whilst I was finishing my previous project, Climbing Days. The alpine cabins and family discoveries of that book opened my eyes to architectural outliers and my father’s strange and remarkable life in the years leading up to my birth… both these things inspired Outpost’s questing nature.

In terms of how I chose the places to which I travelled, each rather led on to the next and I let that happen — either at the time I was at one location and thought of another, or somebody suggested a wild far-flung place they loved, or an image inspired me — as was the case with MDRS in Utah. For example, in setting out to find cabins near volcanoes (where might such places exist?) and discovered the sælhús of Iceland. I knew that I wanted to visit a lighthouse and a little research revealed that Phare de Cordouan was the last manned marine beacon in Europe which could be visited by the public. That trip got me thinking in new ways about beacons and keepers, vedettes and messengers, outposts as “sites of illumination” — something I unpack a little in the book’s epilogue. Also, I was keen not to repeat myself and so, as Outpost went along, I began to think “what haven’t I written about yet? What’s missing?” … but the fact that Svalbard bookended the project, the shape and symmetrical symbolism of that, was set very early on.

This emphasis on putting pen to paper first, it’s so true how it can feel most natural (and productive) to work through ideas and hash out all their possible forms manually before moving onto computers or other machinery.

Wendell Berry (whose poem “The Peace of Wild Things” acts as Outpost’s epigraph) has written brilliantly and movingly about the idea of book as palimpsest in his 1987 essay, Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer:

The act of writing language down is not so insistently tangible an act as the act of building a house or playing the violin. But to the extent that it is tangible, I love the tangibility of it. The computer apologists, it seems to me, have greatly underrated the value of the handwritten manuscript as an artefact. I don’t mean that a writer should be a fine calligrapher and write for exhibition, but rather that handwriting has a valuable influence on the work so written. I am certainly no calligrapher, but my handwritten pages have a homemade, handmade look to them that both pleases me in itself and suggests the possibility of ready correction. It looks hospitable to improvement. As the longhand is transformed into typescript and then into galley proofs and the printed page, it seems increasingly to resist improvement. More and more spunk is required to mar the clean, final-looking lines of type. I have the notion—again not provable—that the longer I keep a piece of work in longhand, the better it will be.

To me, also, there is a significant difference between ready correction and easy correction. Much is made of the ease of correction in computer work, owing to the insubstantiality of the light-image on the screen; one presses a button and the old version disappears, to be replaced by the new. But because of the substantiality of paper and the consequent difficulty involved, one does not handwrite or typewrite a new page every time a correction is made. A handwritten or typewritten page therefore is usually to some degree a palimpsest; it contains parts and relics of its own history—erasures, passages crossed out, interlineations—suggesting that there is something to go back to as well as something to go forward to. The light-text on the computer screen, by contrast, is an artefact typical of what can only be called the industrial present, a present absolute. A computer destroys the sense of historical succession, just as do other forms of mechanisation. The well-crafted table or cabinet embodies the memory of (because it embodies respect for) the tree it was made of and the forest in which the tree stood. The work of certain potters embodies the memory that the clay was dug from the earth. Certain farms contain hospitably the remnants and reminders of the forest or prairie that preceded them. It is possible even for towns and cities to remember farms and forests or prairies. All good human work remembers its history. The best writing, even when printed, is full of intimations that it is the present version of earlier versions of itself, and that its maker inherited the work and the ways of earlier makers. It thus keeps, even in print, a suggestion of the quality of the handwritten page; it is a palimpsest.

I’m really drawn to this. It reminds me of the Arts and Crafts movement, and I like how it respects the creative process — that ideas are tangible and their evolution into writing is its own materiality felt by the reader, even when those ideas have been reduced and unified into monochromatic type on a page. There’s a cross-cultural, timeless magic to that.

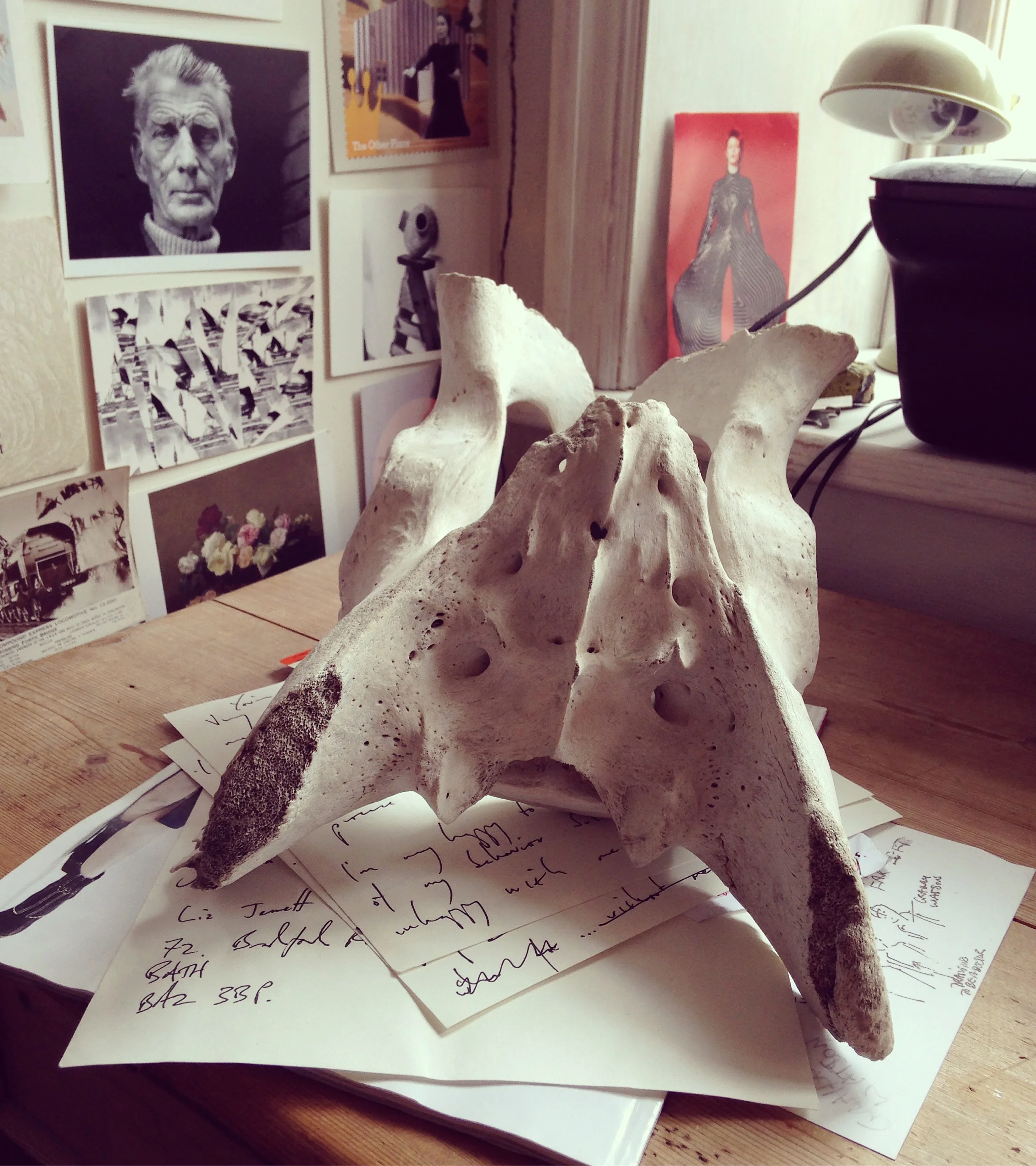

“I grew up fascinated by the polar bear pelvis in my father’s study. My mother, Annie, tells me that when my father, Tim, returned from his final Arctic expedition, a month before my birth, it was night and raining hard … Next morning he unpacked his bag. Everything smelled of smoke. The smell permeated the whole house — Trangia smoke and unwashed man — and from deep in the stuffed mix of wool and down he drew out the pelvis, abstract, sculptural, bleached, and placed it on the table. Strange object from another world.” (Outpost, p.2). Photograph: Dan Richards

I appreciate how the weight of your stories orbits the effects and interrelations of hinterlands on and with humans, rather than a book about wild places in isolation, humans removed. Your stories offer glimpses into lesser-known occupations within those wild places: a caretaker at Ferðafélag Íslands, a fire lookout at Desolation Peak, a researcher at MDRS Utah, an Arctic guide, and others — including yourself as a writer. In every chapter there is your own account of each place and event but also stories belonging to other people and their embedded experiences of these places. Did you ever feel pulled amongst the overlapping stories when you were writing and editing?

Everything I do is about story. I try to be a conduit and tell other people’s stories as best I can whilst relating my own thoughts, experiences, and adventures. I’m keen to get away from things I already know, places I’ve already been, thoughts I’ve already had — the next thing, the new thing; that’s what excites me. I think interest and trust are key — genuine curiosity is a generous thing and I think people respond to it. People tell me things. Perhaps it’s my eccentricity and affable, inquisitive appearance in their midst, I don’t know — the nurse in Iceland en route back from Landmannalaugar is a good case in point; people become confessional. However all this makes it paramount that I tell people’s stories and report their words with accurate fidelity. That’s crucial or else all good faith is lost. Therefore, in answer to your question I would say that, where contradictions and confusion exist, I do my best to elucidate, tease out, and comment. I love writing with clarity and pith. A lot of my favourite writers are succinct and that’s something I aspire to — the poet’s economy. The fizz, spank, and shock of an apt image delivered in a couple of words. I try always to be interesting whilst also exact in my quotations. As much as anything else, I think it’s true that fact is often times more surprising than fiction!

Shedboatshed (Mobile Architecture No. 2), Production Stills, 2005. Photographs: Simon Starling; courtesy of Dan Richards

I was warmed by your accounts of strangers’ unsolicited gestures of honesty and openness, their brief but intense confiding in you. Fellow writers sharing their lives and stories. I like this on p.228:

IN ADDITION TO SIMPLICITY NUDITY

H D THOREAU

“Desolation Peak, WA, USA” reminded me of my own high school camping trips in the Pacific Northwest. I liked how such stories depicted overwhelming “wilderness” on our “humanness” — the wild seems to render us, regardless of age, rather plain and vulnerable, awkward and afraid without our everyday comforts. And how, sometimes, we are simply ill-equipped to face the sheer solitude we meet in the wild. It made me think about how outposts force us to relinquish our habitual moorings, so we find ourselves excitedly drawn to (or mooring ourselves to) found tokens of humanity: a clapboard shack in the distance, a tin-roofed hut with a small stove, and one another (even better if complete strangers), wherever possible, however briefly, instinctively.

I was also surprised by the countless people who came to your aid, time and time again. Hitchhikers, strangers, old friends joining on risky hikes, acquaintances you hadn’t seen in over a decade responding to you by reaching out to their friends, then their friends of friends driving out to meet you in the middle of nowhere.

It’s wonderful, all the more so because it’s unexpected. I always hope people will be hospitable and good samaritans — to myself and fellow travellers (fellow non-drivers in Iceland and Utah!) — but I never take it for granted. One of the great wonders of kindness is its unexpectedness, the fact it comes from a gracious place, a blessing. But, as in Utah, we live in a very connected world now so, as well as grace of strangers, we can invoke and summon the wisdom and help of friends wherever they are in the world — I was able to hop onto WhatsApp to phone a friend in Shanghai, then search Facebook to find a friend in Helper… its amazing to live in a networked world.

What would travel be, particularly to remote locales, without hospitality in all its various forms?

Cold in most every sense!

What might life be like, if we were all willing and able to shed our thick, comfortable cloaks?

Kinder, warmer, closer, better.

Do you think this kind of connection is only possible on travels?

No, but I think travel kindles the writer in a lot of people. We send analogue postcards from a foreign post office, we write emails to groups of friends, we start an Instagram stream…

Do we need the wilderness to accomplish this freeing, spontaneous connection with others?

Well, of course it also has to do with time and having the chance to write — I write a lot on trains here in the UK (another of the opportunities afforded by not driving a car) but there’s no doubt that, as well as broadening the mind, travel opens us up and reveals our place, microcosmic size in the great wide world, and feeds a hunger to connect.

“In early 2016 I saw a picture of MDRS on the front of a magazine named Avaunt, a picture of an astronaut walking into a red world of rock and ice, a skyline of blue mountains, and I thought, ‘Mars! Now there is the ultimate outpost, the final frontier of exploration and cabins… because we’ll have to live somewhere when we get there… which we haven’t yet — so where was this photograph taken?’” (Outpost, p.125). Photograph: Dan Richards

Throughout Outpost, you show us how human experiences of remoteness can be very profound (such as the “overview effect”), but they can also fall very short of our restless ideals (as you mention Kerouac’s experience, for example). British sociologist John Urry wrote about the “tourist gaze” (1990), about how we often rely on cultural stories passed down by others, movies, songs, social media, news portrayals, personal interpretations, (etc), to construct an ever-evolving, experiential image in our minds of what it might be like “over there.” We actively and unknowingly accumulate bits and pieces for later reference. He argues that we bring this embodied gaze with us to the places we travel to, and that our gaze ultimately frames our experiences within those destinations. It may be arriving to a campsite then exclaiming, “‘we can’t camp in this beastly place ... Blast all Englishmen!’” as William Morris had in Iceland (pp.21-22), or the way Sergey Chernikov explained how the people who live in Pyramiden are not political but, “It is British people and Westerners who are interested” (p.263). It may also be your arrival in the Pacific Northwest to follow the words of Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Denis Johnson, and wondering if this is what they saw and felt too (in “Desolation Peak, WA, USA”); or your experience of Nageire-dō, “just as I’d seen it in pictures, only now, up close, its presence was electric” (p.245); or your residency experience in Switzerland, “I can’t help but compare my glossy box with Roger’s shepherd hut” (p.222).

It’s very interesting what you say. The idea of the gaze is something I mention in the epilogue with reference to the polar bears — John Berger’s thoughts on looking at and photographing animals — I’m aware that gazes are double-edged and cut both ways. You’ll note that in his desire for an “authentic” experience of integrity (whatever that means; more problematic and knotty terms), William Morris rebels against his well-meaning guides. They wish him to have the tried and tested tourist experience which so delighted his fellows but this is exactly what Morris wishes to avoid, “the tourist route”, the package tour… authenticity for him lies in a mixture of the lived Icelandic humdrum and the magical little visited wild. Of course this is still the case — something I tried to get across in the book — and the sight of one’s fellows in a place where one wishes to be a frontiersman, naive and impossible as that is, still prompts ire, chagrin, and shame. Funny how the rubbish left by one’s fellow Englishmen is more shameful than the trash left by mere “people”. National guilt is personal and cuts deeper. I felt it too. My feelings were very close to Morris’s. I think the “overview effect” is a close relation of the wishes to be alone and leave no traces — either as an individual or species.

MDRS, Utah, USA. Photographs: Dan Richards

I’m curious if there there were experiences during your travels for Outpost, whether en route or at the destination, which greatly challenged or subverted some of your preconceptions of those places? Can you tell me a bit more about these?

Many of the outposts I visited were vital, germane, peopled, and connected. Any assumptions I had about their obsolescence were misplaced and quickly disabused. The sæluhús are in constant flux of renewal and Ferðafélag Íslands are working wonders with the thirty-seven they oversee. Cordouan is a modern beacon, part of a global network of shipping; Jim Henterly acts as a key link and radio dispatcher to people in the deep Cascades; the bothies of Scotland are full of charged memory and the recent human traces; Pyramiden may be mothballed but it’s vital and cared for — indeed, its curation is held up as an example of best practice.

When you arrive at a place with the intention of writing about it, does this approach naturally change your everyday perspective and approach to your surroundings?

I love being surprised and passing that wonder on to my readers. I think prejudice hinders good travel writing because the author runs the risk of writing about their jaundiced preconceptions rather than the reality. Confirmation bias a killer to good reportage.

At times do you find yourself writing with the aim to further challenge (or affirm) stereotypes of a place?

Affirm, no. I hope not, anyway. Challenge or look slantwise at them, certainly. I want to explode my reader’s view, knowledge and interest in a place rather than closing it down with caricatures or clichés. That’s lazy and reductive. When I go somewhere, I go to learn rather than preach from a position of assumed knowledge. I want to be disarmed, puzzled, and maybe awed by unexpected developments. I want to be disabused of stereotypes.

I think book learning is kindred and symbiotic to empiric experience — you need both for a full picture. Neither has preeminence and the trope of the white man arriving somewhere to tell people who live there how it is is something that needs to be dismantled as soon as possible. To this end, perhaps, I subvert the idea of “travel writer as wise guide” — I don’t think I’m capable of writing that sort of thing. I don’t believe in it, for one thing, but I really can’t take myself that seriously. My books are full of humour, farce, and missteps. I lay bare my deficiencies: I’m honest when I’m mistaken or out of my depth and such things make the books fun and relatable, I think, because that’s life! Hopefully, Outpost is both scholarly and funny; enlightening and amusing — a spoonful of sugar and all that…

Were there places or moments which felt almost sacred, that had you hesitating or questioning whether to include/omit them from your final work for fear of what might become of it (“otherness attracts scrutiny” as you write on p.226)? Or, even a place where human words might feel misplaced?

Words, no. People, yes; and I tried to untangle those ideas in the epilogue. I’m not sure if I succeeded but I tried. Outpost has “flygskam,” “leave no trace,” and “do no harm” written on its heart.

投入堂 Nageire-dō, Japan. Photograph: Dan Richards

Fuhrimann, Fondation Jan Michalski pour l'écriture et la littérature, Switzerland. Photograph: Tonatiuh Ambrosetti

On this note, your book grapples with anthropocentrism, each chapter building up to a crescendo of questioning humanity’s place on Earth. You address the paradox of travelling to remote places for these very life-changing experiences and, throughout the book, there seems to be a sort of torment — a pull between thrilling and disheartening, a personal loving-loathing. For instance, on your encounter with other visitors zipping across on snow mobiles in the Arctic, you write (p.273):

... it wasn’t normal, it was more a resigned acknowledgement that they were here too. ‘Here we are,’ my wave said. ‘Here we all are ... too many. But it’s nobody’s fault; it’s everybody’s fault. Here we are.’ And all the time I had the image of those poor bastard bears swimming out to ice that didn’t exist. The spectre pursuing me over the snow. I couldn’t shift the sadness ...

I’d travelled to the end of the world to discover that there are too many of us travelling to the end of the world — I mean, who saw that coming?

Upon completing this book, has your residual sentiment since leaned more optimistic or pessimistic? Have you arrived at any new (or renewed, urgent) conclusions or discoveries about humanity and our possible role within wilderness? Or, perhaps hopes for the role of writing in wider needs, movements, crises of our times?

Everybody needs to do more. Laws need to change so green alternatives become the norm. Legislation needs to be put in place to make rail travel cheaper than road. Electric trams and trolleybuses need to make a comeback. Petrol and diesel cars need to be phased out as a matter of urgency. Electric cars are coming down in price… but urgency is the word here. Air travel is too cheap for the damage it’s doing the Earth — damage dwarfed by container shipping, something which often goes unmentioned. Transport needs to be taxed based on how much they harm the environment… and thankfully things are beginning to gather pace on that front — only today, Mohammed Barkindo, the secretary general of the trillion-dollar Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) opined the growing mass mobilisation of world opinion against oil, which was “beginning to … dictate policies and corporate decisions, including investment in the industry”. “Greta Thunberg and other climate activists have said it is a badge of honour that the head of the world’s most powerful oil cartel believes their campaign may be the ‘greatest threat’ to the fossil fuel industry.”

We need to all plant more trees, stop using lethal industrial pesticides that kill bees, slash our use of plastics… and we know this but it’s not happening fast enough. We’re all hypocrites. We’re all deniers in one way or another — I comfort and kid myself on a daily basis. But the sense of climate emergency is mounting and when a fever pitch is reached I believe change will come. There is hope in people but we need to be better and we need to be better custodians and think longer term. We’re a very short term species — like a virus; we consumer. We need to change that and, to go back to what was just said about networks, we need to acknowledge how interconnected everything is.

Keeping cups, shunning single use plastic, and flying less won’t be drops in the ocean if we all pitch in and rain; if we all make a concerted effort to turn the tide. Dog sledding is better than snow mobile-ing. The overview effect is just that: holistic. So I do see hope, as well as believe that people will continue to travel; we just need to be more mindful of what we’re doing and how.

We need to think and balance our actions with the planet’s greater good and that’s something I tried to communicate in Outpost — flawed and riven with contradictions and hypocrisy as that maybe. It’s a start, I think. I choose to believe there is hope.

Isfjord Radio, Svalbard. Photograph: Alex Edwards

Polar bear print and wool glove on frozen Billefjorden, Svalbard, 2018. Photograph: Dan Richards

Steve King approaching Hutchison Memorial Hut, Cairngorm Mountains, Scotland. Photograph: Dan Richards

Jim Henterly and Dan Richards, Desolation Peak Lookout, WA, USA. Photograph: Colin Cady

Ideal setup on-the-go: Mostly I’m writing in my notebook wherever I happen to be — travelling, having stopped somewhere — I make notes and jot down speech and observations whenever and wherever possible. I did write in Roger Deakin’s shepherd’s hut and at FJM in Montricher, Switzerland but these were spaces already set up and attuned to writing (by which I mean, there was a desk and a chair). Otherwise I was walking around and scribbling like a reporter; in fact, I can tell when I was particularly hard-pressed and writing on-the-go because in those sections only the right-hand pages of my notebooks have been used — pen held in right hand, book held in left.

What do you need to be productive? Daytime — a desk, a pen and paper, (mac if the book is further along), powerpoint (mac battery is unreliable), relative quiet — a bit of background hum is fine, tea/coffee. Evening — as above but with wine instead of tea/coffee.

When and where do you prefer to write? I write in the evenings if the writing is going particularly well/badly — i.e. is particularly fun and I’m keen to run with it or is going particularly badly and needs fixing — if the day’s been particularly hot or I’m up against a deadline — which can be good, deadline pressure is a good driver sometimes. At the moment my writing space is a desk in Bath or a table in Vevey, Switzerland. There’s a good cafe in Waterloo, London, where I sometimes work too. Again, coffee is important.

I feel compelled to ask… upon returning home, do you have a trusted outpost which you necessarily frequent; your own version of Dahl’s garden shed, Deakin’s shepherd’s hut, Thoreau’s cabin, etc? Not at the moment, but I’d love one — let’s call it a work in progress.

Outpost: A Journey to the Wild Ends of the Earth

by Dan Richards

"There are still wild places out there on our crowded planet. Through a series of personal journeys, Dan Richards explores the appeal of far-flung outposts in mountains, tundra, forests, oceans and deserts. These are landscapes that speak of deep time, whose scale can knock us down to size. Their untamed nature is part of their beauty and such places have long drawn the adventurous, the spiritual and the artistic. For those who go in search of the silence, isolation and adventure of wilderness it is – perhaps ironically – to man-made shelters that they often need to head; to bothies, bivouacs, camps and sheds. Part of the allure of such refuges is their simplicity: enough architecture to keep the weather at bay but not so much as to distract from the natural world. Following a route from the Cairngorms of Scotland to the fire-watch lookouts of Washington State, from Iceland’s ‘Houses of Joy’ to the Utah desert; frozen ghost towns in Svalbard to shrines in Japan; Roald Dahl’s Metro-land writing hut to a lighthouse in the North Atlantic, Richards explores landscapes which have inspired writers, artists and musicians, and asks: why are we drawn to wilderness? What can we do to protect them? And what does the future hold for outposts on the edge?"

Available at Canongate Books.

Published: 4 April 2019. Hardcover: 336 pages.

Cover photo: Paul Webster/WalkHighlands.

Published on 17 July 2019. Edited by Fields in Fields. All images courtesy of Dan Richards, with quoted captions from his book, Outpost: A Journey to the Wild Ends of the Earth; the cover image of this feature was taken by Dan’s father, Tim Richards, at "Hotel California," Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard, 1982. ■ Dan has also written The Beechwood Airship Interviews and Climbing Days, and co-authored Holloway with Robert McFarlane and Stanley Donwood. Follow along @dan_zep.